Last month, YouTube celebrated its 20th anniversary, and a couple sites marked the occasion by going through the platform’s 10 most viewed music videos. While we appreciate the music video coverage, it’s all been pretty surface level - some light nostalgia and easy dunks on Ed Sheeran. But the real story isn’t what’s on the list. It’s why the list hasn’t changed. So instead of roasting old videos, we traced the rise and collapse of the Vevo bubble, and how YouTube’s pivot from ad-supported music videos, to a hybrid model that includes subscriptions and UGC monetization, hollowed out the music video industry for a second time.

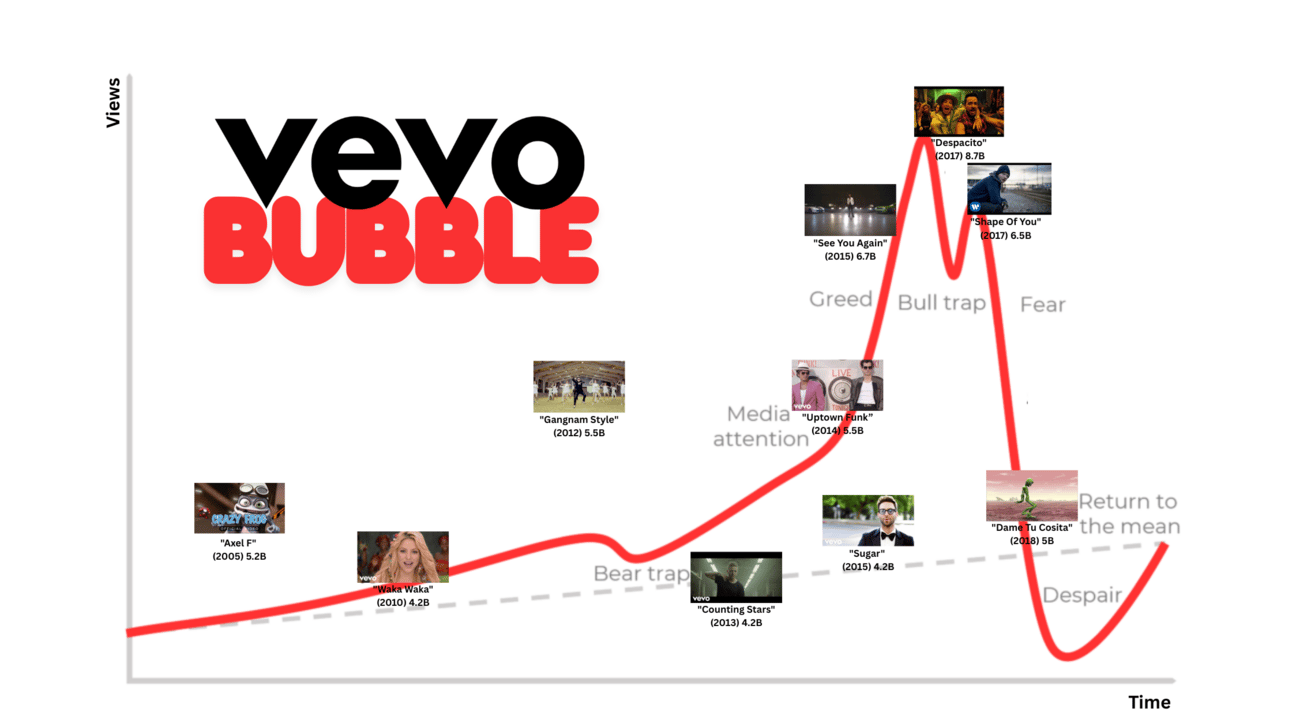

I don’t think anyone sees a list that features Maroon 5, Charlie Puth, and OneRepublic and says, “this is when our culture peaked.” What this list represents is a time capsule of an era when music videos were the priority content on YouTube. This isn’t a greatest hits list, it’s a sediment layer. A fossil record of Vevo-era homepage takeovers and autoplay momentum, preserved by an algorithm that has moved on to UGC.

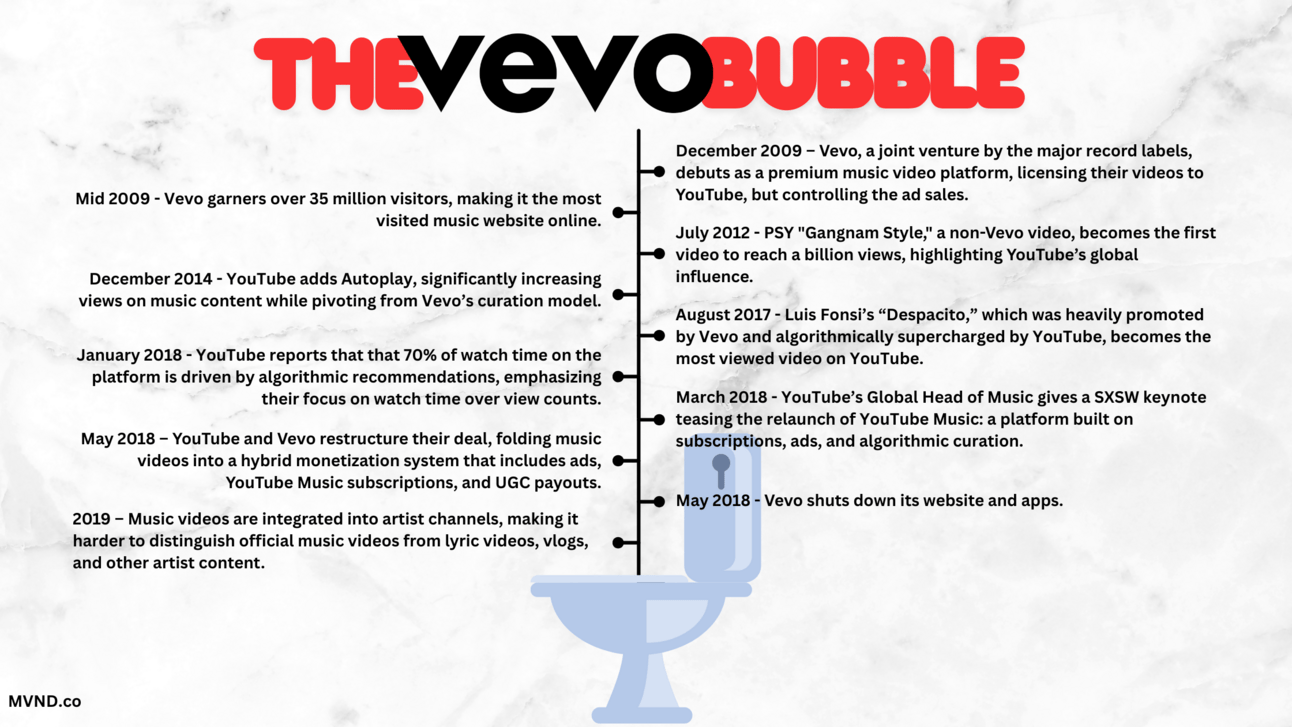

The turning point was 2018 - the year YouTube relaunched YouTube Music, restructured its deal with Vevo, and quietly dismantled the infrastructure that the industry was built on.

Before that, Vevo was the closest thing to a premium layer YouTube ever had. Dedicated players. Curated launches. Actual editorial. A sense that music videos were an event, not just another upload.

Launched as a joint venture between the major labels in 2009, Vevo’s goal was to license and monetize official music videos on YouTube and other platforms. Labels had control over ad sales, curation, and branding while still riding YouTube’s scale. Initially, Vevo only monetized official, high-production-value music videos and rarely featured live performances, lyric videos, or BTS content. That exclusivity gave the format a kind of cultural weight, and also brought online a lot of legacy videos that were lost to the MTV-era.

Vevo quickly became synonyms with music videos online, and was the most popular music website in the US just a few months after launch. Although it wasn’t the home for all music videos, and sometimes that stood out. From the Verge in 2012:

Psy’s “Gangnam Style” has officially become the inescapable smash hit of 2012, and last month was officially anointed as the most popular video in YouTube’s seven-year history. Yet if you were merely judging the song by it’s success on Vevo — the website specifically created by record labels to be the premier destination for music videos — you’d have no clue of its pop culture significance. That’s because, as the New York Times reports, Vevo lacks a licensing deal with the South Korean record company that first released “Gangnam Style.” So even as the song soared up the iTunes sales charts and drew hundreds of millions of views on YouTube, it was nowhere to be found on the industry-backed site.

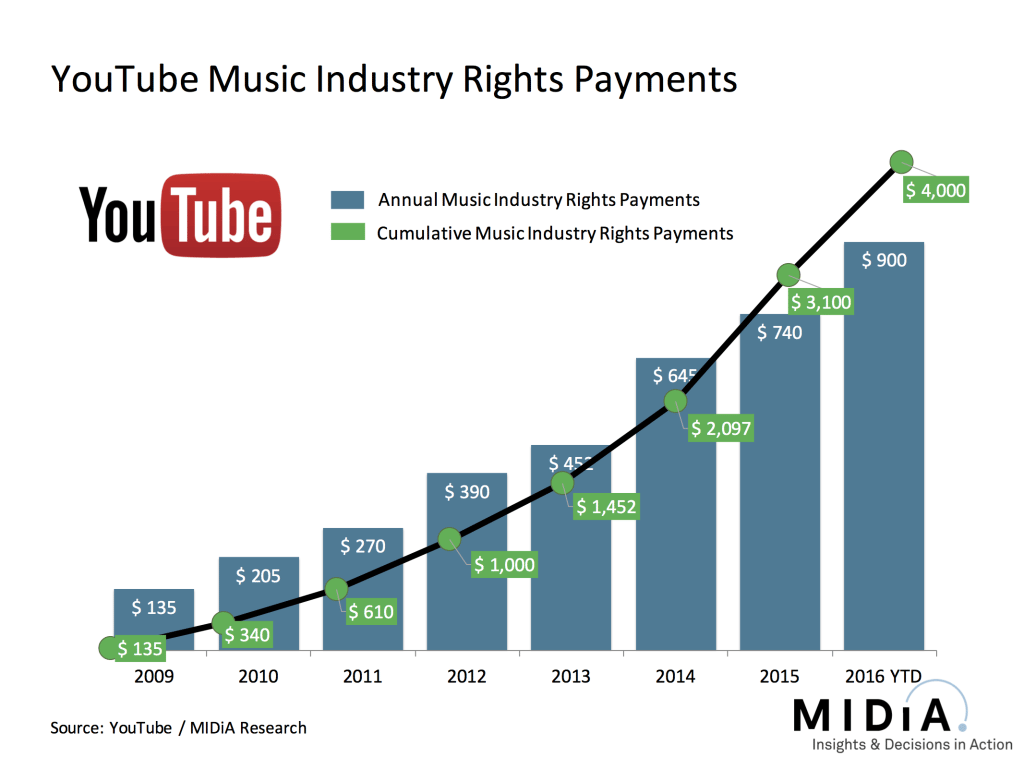

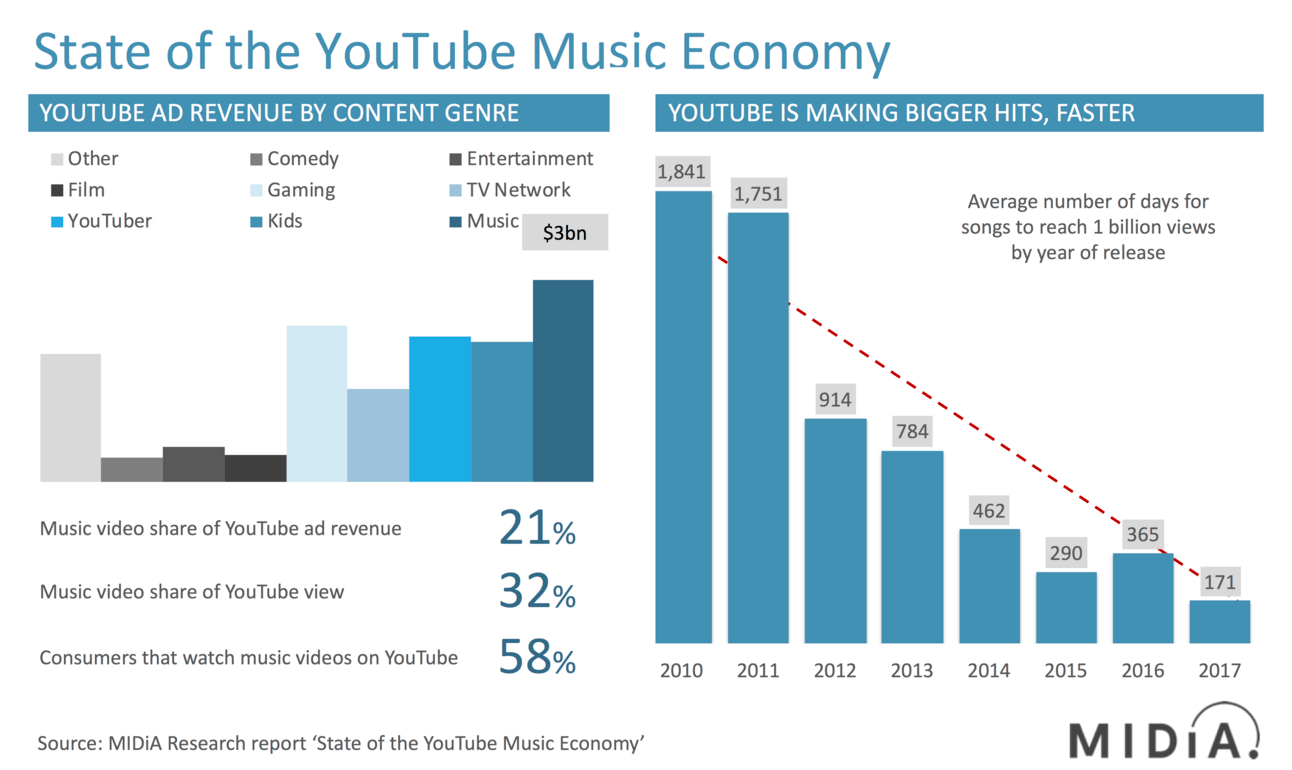

In late 2014, YouTube introduced autoplay, which significantly increased views on music videos, while also pivoting away from Vevo’s curation model. Despite this rapid and continued growth, by 2016, the relationship between YouTube and the labels was tense. Vevo wasn’t profitable, and the labels felt like they weren’t getting a fair share from YouTube streams. According to Midia research, while “YouTube music streams increased by 127% in 2015, ad supported music industry revenue only increased by 11%.”

YouTube was paying billions of dollars to the music industry, but it was still far behind platforms like Spotify, which labels called the YouTube “value gap.” In response, YouTube tried to find creative ways to cut labels in on additional ad revenue. While initially only monetizing official music videos, YouTube eventually started using their content ID system to find videos using licensed music, and would allow the labels to monetize other user’s content if it used their song. By 2016, YouTube had paid out over $2 billion to labels through the content ID system alone.

The thing about YouTube views is it is an entirely fake metic. YouTube doesn’t just measure views, it defines them. There’s no third-party audit, no transparent accounting. One tweak to autoplay, one shift in how recommendations are served, and suddenly a video gains millions. Is a view counted when someone finishes a video? Or every time someone starts a video? That’s entirely up to YouTube.

YouTube and Vevo kept pumping more and more views into music videos, breaking view records faster and faster each year. Luis Fonsi ft. Daddy Yankee "Despacito" was released in January 2017, and by August it was already the most viewed video on the platform. The view pumping had reached a peak, but YouTube was still paying significantly less per stream than its competitors.

By 2018, YouTube accounted for nearly 50% of all music streams, but only 7% of music industry revenue. That value gap - billions of streams earning fractions of pennies - wasn’t just frustrating, it was insulting. Labels watched vinyl bring in more money than their most-watched videos. They weren’t just annoyed. They were preparing an exit.

In January 2018, YouTube reported that 70% of what people watched on the platform was recommended by their algorithm. Users were no longer in control of their video consumption, YouTube was. Lyor Cohen, YouTube’s Global Head of Music, and former artist manager slash label exec, began shifting his messaging away from traditional music videos. This coincided with YouTube's strategic pivot toward a hybrid revenue model that featured subscriptions, advertising, and UGC.

Later that year, at a keynote at SXSW, Cohen discussed YouTube’s plans to launch a new music subscription service, YouTube Music; highlighted the integration of Google's recommendation algorithms; and hammered the importance of both ad-supported and subscription-based revenue streams.

Vevo had always felt like a temporary solution that was trying too hard, and no one was happy with it. So the stage was set to kill it off, along with the music video industry as we knew it.

For YouTube, they wanted something scalable. Vevo was a holdover from when labels had leverage. Killing it allowed YouTube to own the full monetization stack: inventory, distribution, ad sales, UX, and metrics.

The labels were looking for predictable payouts. Vevo’s flash didn’t translate into dependable revenue, but YouTube’s new hybrid model promised it would. So they traded cultural impact for quarterly consistency. It was fine to deemphasize music videos and treat them the same as any of the other slop content hosted on YouTube. They just needed the line to go up.

The same year, YouTube and the labels restructure their deal, folding music videos into the new hybrid monetization system. Vevo shut down their standalone website and apps. Music videos got integrated into artist channels, making it harder to distinguish official music videos from lyric videos, vlogs, and other artist content.

Cohen ended his year like he always does, recapping YouTube’s payments to the music industry, strategic initiatives, and future goals in an open letter. This time, he featured a conversation with music video director Karena Evans. Praising music videos and the humans behind them from one side of his mouth, while orchestrating the gutting of the industry from the other.

So where do we go from here? If you ask Lyor Cohen, the answer kind of sucks. In March 2025, he was asked the long term future of music videos on YouTube, and this is what he said:

Thank you for asking that question, because that is one of our top priorities: visual storytelling. I’m thinking [a lot] about the music video. You know, the living room is the fastest-growing screen [for] YouTube.

There’s a lot of incredible and positive signs we have about the opportunity of video and storytelling. There’s a lot of [music] releases per day, and so we think that video storytelling really helps contextualize songs.

We’re not interested in just breaking songs. We want to break artists, and video storytelling is one critical foundation block.

It’s also been the most costly line item of the music industry. If there is a way through AI that we could help reduce the cost of visual storytelling and improve the quality, I think it would be a real gift that we could give our partners and artists and fans.

Certainly we’re doing a lot of work on discovery and making sure that the Premium music video and storytelling is front and center and we’re very excited about it.

This reply went from good, to bad, to terrible in like 2 seconds. The fact that any human-created music video gets made in 2025 is a miracle. YouTube’s Global Head of Music has been actively undermining them since joining the company in 2016. Cohen’s background in the music industry was supposed to signal that YouTube was serious about nurturing the relationship between YouTube and the labels. But the idea that generative AI is going to improve the quality of visual story telling is the most unserious answer he could have given. Especially for an art form that often relies heavily on the physical presence of a musician. Someone to look cool, or hot, or weird, or even just alive while performing the song.

Music videos have never lost cultural relevance, they have only lost structural support. What used to be the centerpiece of an album campaign became nothing more than a costly line item. And yet, they keep getting made. Despite powerful people fighting against them, they still break through and move culture forward. While the days of the 8 billion view music video may be over, videos are still setting records for vitality and view counts. Just this year, “APT.” by Bruno Mars and Rosé broke the record, previously held by "Gangnam Style," for fastest K-pop video to reach a billion views.

Music videos have always been the most effective tool for artist development, longevity, and audience building. They’re the only way for an artist to truly contextualize their music online, before TikTok get’s their hands on it and reduces it to a meme. They will continue to break records, drive culture, and dominate YouTube far longer than Lyor Cohen will. Or as Bruno Mars would say, don’t believe me just watch!

“Come on!”